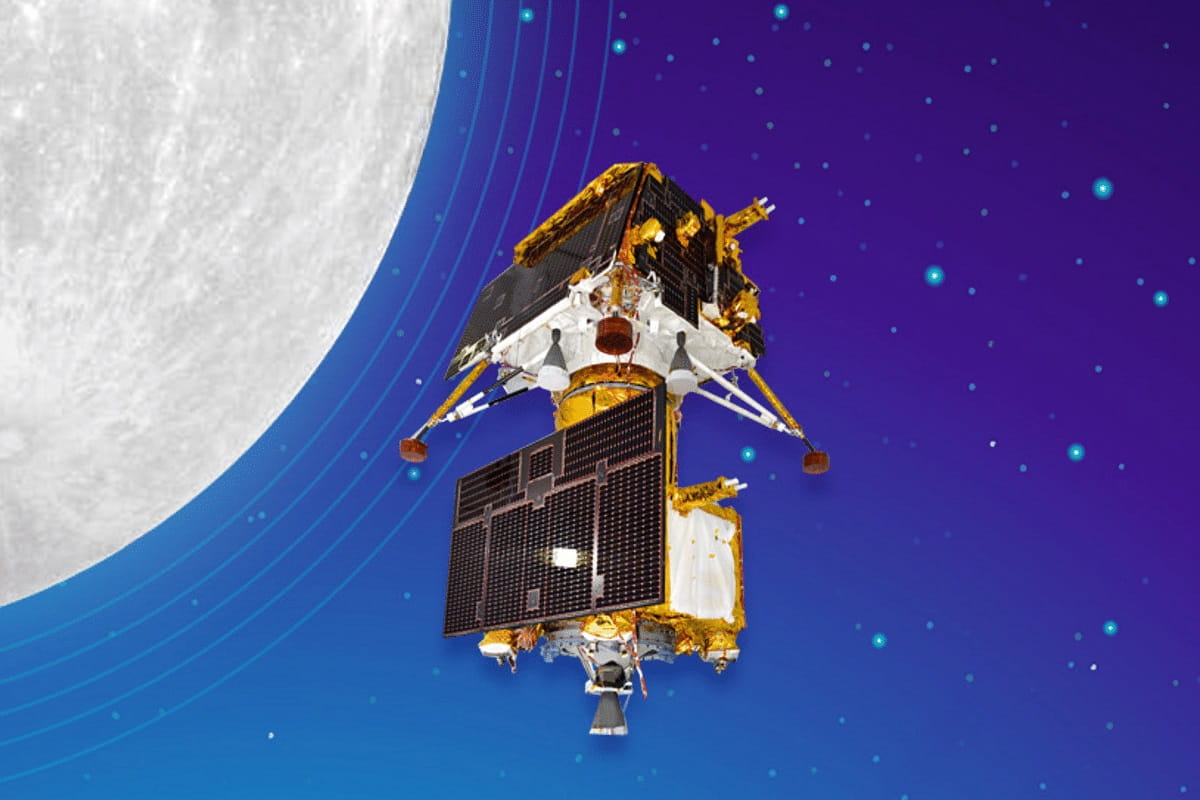

ISRO’s Chandrayan-3

On August 30th, 2023, the first pictures from the moon showcased not just the capabilities of India’s Chandrayaan 3 mission but its capability to successfully improve on the Chandrayaan 2. The success was the result of a 20-year journey of improvement.

If innovations are defined as the improving of something - either physical or intangible, and then designing, developing and delivering the improvement in some physical form, how many innovations from India, from any field, would come to mind from the last 1000 years? Last 500? 100? 50? 25?

Why is it so hard to name such innovations? Surely not because nothing needed to be improved upon! Why is it that in spite of profound contributions to the world’s understanding and knowledge in areas ranging from mathematics to medicine to surgery to astronomy to metallurgy to philosophy, logic and grammar, innovating to make something better, faster, cheaper for people and society has been absent?

Innovation is midwifed by the socio-cultural-economic ethos of a place. It isn’t specific to formal education, a class, a market, laws, ideology, capital, patent or property rights as historians of innovation like Dr Anton Howes have argued, though these are important ingredients. It has been said that Silicon Valley is not a place but a mindset. It transcends the talent, the funds, the educational institutions, and service providers; It is about learning, open-ness, collaborating, experimenting, improving, helping, mentoring, of paying-it-forward: a culture of innovation.

Tipu Sultan’s rockets that caused mayhem among the British East India Company army in the 18th C were improved upon by William Congreve and used later by the English against the Americans as Congreve rockets! Why weren’t these rockets improved upon in India? Or, why were not the pioneering globally renowned Wootz carbon-steel alloys used in swords that led to Damascus steel and then, after European scientists got to work on it, contributed to the creation of the modern European metallurgical and arms industries, improved upon in India? While the 11th C Yukti Kalpataru details ships and ship building and Indian navies scored remarkable victories e.g., Marthanda Verma’s defeating the Dutch in 1741, and Indian seafaring expeditions to South-East Asia show the capabilities of Indian ships, these didn’t translate into a powerful naval presence, unlike in Europe, where naval power served commercial, deterrence and offensive purposes.

The roller cotton gin from India - India was globally renowned for cotton - was substantially improved upon in the 18th C by Eli Whitney and others led to the US becoming a cotton powerhouse.

Elsewhere too, though there were the odd polymath inventors and innovators like the 9th century Persian Banu Musa brothers (“Book of Ingenious Devices”) or the 11th century Chinese Su Song, there was no culture of innovation that was established.

Why then did this mindset first emerge in Europe and not elsewhere? Why didn’t India, China, Japan or anyone else develop this culture of innovation?

There were a series of unconnected, overlapping and ultimately convergent social and cultural developments in Europe that led to the creation of the innovation mindset.

Natural Philosophy: the result of polymath philosophers and theologians like 13th C Roger Bacon placing great emphasis on the study of nature and the gathering of facts before reaching conclusions. His work was encouraged by his benefactor Pope Clement IV to have “writings and remedies for current conditions”. This involved seeking evidence through experiments and observations rather than on intuition or revelation, being unafraid to fail and continuing to iterate. Knowledge therefore began to be seen not as absolute but continuously evolving based on evidence. Science without scientism, and separate from religion, this empiricism was at the root of the creation of Natural Philosophy, the study of nature and the physical universe: Newton’s seminal 1687 book is titled the Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. The addition of science to the traditional curricula in medieval institutions contributed viz. Roger Bacon’s enablement of optics as a subject in universities ultimately led to the creation of spectacles.

Tools and Instruments: A natural and critical offshoot of engaging with the natural world is the creation of tools to help us better learn, experience and analyze the world around us. Our existence today is a result of the bewildering range of tools that surround us today in every aspect of our lives. The 15th C creation of the printing press by Gutenberg, credited with the onset of the modern “Information Revolution”, is an example of a tool.

Marketplace of Ideas: the dissemination, borrowing and improving upon ideas from all over. The development of the steam engine, credited with starting off the Industrial Revolution, is especially illustrative of this. In 1606, Spaniard polymath Jeronimo Beaumont’s steam powered water pump used to drain inundated mines in Spain was the result of a long line of unknown experimenters who had worked with steam to power fountains. In 1690 Frenchman Denis Papin published a paper in the Acta Eruditorum, the first German scientific journal, that described how “considerable forces’ could be obtained from steam to lift a weight, was the result of his working with Robert Boyle (of Boyle’s Law fame) at the Royal Society where his papers were presented. Thomas Newcomen, in 1712, improved on Papin’s design and produced a working engine that could have repeatable actions. The Newcomen engine was manufactured and used across England and even in France for mining, furnaces and cotton mills. John Smeaton and James Pickard then further worked on this engine with Pickard obtaining a patent for his innovation. Innovating further, James Watt, in partnership with Mathew Boulton increased the efficiency of the Newcomen engine and became celebrated.

As Sir Isaac Newton said, “if I have seen further [than others], it is by standing on the shoulders of giants” (and this statement itself has been traced to the 12th Century!). A system developed that allowed the foundation of a marketplace for ideas for innovation and improvement to occur.

The important properties of the “marketplace of ideas” worth keeping in mind.

- Innovations were led by citizens, individual intrepid resilient innovators, who loved to tinker and improve things. Two bicycle mechanics created the first motor powered plane!

- There were funders available to fund risky ventures.

- Innovations were accelerated through combinatorial means. For example, the study of optics to lenses and mirrors to spectacles to magnifying glasses to telescopes to microscopes and so on.

The presence of an active culture of written documentation, presentation, and iteration was important for the marketplaces of ideas and the innovations arising thereafter as an oral tradition alone would have found it impossible to conceptualize, design, develop, collaborate, and manufacture increasingly complex technological tools and instruments.

Zeitgeist the dominant catalytic beliefs emerging from the socio-cultural environment of the times. Any change is strongly resisted for fear of disrupting the extant order, identities, continuity and harmony. Traditional hierarchical structures and orthodoxy inhibited experimentation, mobility of people and ideas, creation and spread of knowledge and information.

Take the anatomical sciences. While the techniques detailed in the 6th C BCE Sushruta Samhita are still used in rhinoplasty, additional surgical techniques requiring deeper understanding of the human body required cadaveric dissection that weren’t allowed. European anatomical science and surgeries progressed when restrictions were removed by the 13th C Roman Emperor Frederick II and “this initiative was a giant step towards revival of human dissection in the domain of anatomical sciences and towards the later part of the thirteenth century, the realization that human anatomy could only be taught by the dissection of human body resulted in its legalisation in several European countries between 1283 and 1365”.

The kala pani proscription of medieval times is another case in point. Crossing the seas to visit foreign countries to learn, earn, study, document, and to add to the body of knowledge was an important practice seen in Europe from the Italian Marco Polo to the Russian Nikitin and da Gama from Portugal. The Age of Exploration from around the 15th C onwards wouldn’t have been possible otherwise.

Institutions: The establishment of modern institutions such as the joint stock companies with investor shareholders, recognition of patents, setting up of Societies such as the Royal Society in 1660 (the oldest scientific academy in the world) where scientific papers could be presented, debated, commented upon, the presence of contract laws, played a very important role in encouraging and sustaining innovation. James Watt set up a company for his innovation for the steam engine in the 18th C. Johannes Gutenberg had contracts with partners and financers for this invention: a record of a lawsuit involving him and his partners filed in 1455 (he lost!) is still available at the University of Gottingen.

Patents were used by kings to attract private capital to fund ventures based on unproven technology. They evolved from 1421, when the world’s first patent for an industrial invention was granted in Italy, to the 1623 Statute of Monopolies enacted by the UK Parliament that while prohibiting most royal monopolies, specifically preserved the right to “grant patents for inventions of new manufactures for up to 14 years.”

The Industrial Revolution was the result in no small part due to the involvement of private capital and institutions. Our Jagat Seths was not encouraged to undertake funding of innovation.

Worldview The “wounded civilization” of India, as Naipaul called it, withdrew into itself and adopted a defensive insular stance after its experience with violent and destructive invasions by marauding Turko-Afghan armies that from the 12th C onwards destroyed renowned centers of learning (eg Nalanda and Vikramshila) and discourse. The rise and spread of the Bhakti movement during the medieval period, was no coincidence: it focused on, apart from social reform, an individual’s personal devotion as the path to salvation. The emphasis on Bhakti Yoga as distinct from Karma and Jnana Yoga was an important development.

The destruction of indigenous learning and systems, the consequent loss of awareness and self-esteem, coloniality perpetuated under the British ensured that Indian innovations were few and far between.

And those that took place were co-opted by the British. The Bose-Haque system for cataloging criminal records and Radhanath Sikdar’s methods for calculating the height of Everest are cases in point.

In China, the celebrated Chinese admiral Zheng He’s sea faring efforts didn’t gather momentum as the insular policies of the Ming and Qing dynasties eschewed involvement with foreigners, saw itself as the “Middle Kingdom” and, like India, conceded the Age of Exploration. China, though never colonized like India, has not forgotten the “Century of Humiliation” at the hands of the West and Japan. Since 1979, after it “opened up”, China has embraced science and technology, innovation, entrepreneurship, capital and learnt from the West, improved upon and innovated, and become a global powerhouse today, as it develops socialism with Chinese characteristics.

Japan was an insular country during the entire medieval period under the shoguns. The Meiji Restoration (1868 - 1912) saw Japan overthrow feudalism and actively engage with the world. In 1871, a mission was sent to Western countries to learn and craft a template for the development of a modern Japan. Their conclusion was that “technological advances, a fruitful interweaving of trade and industry, and a hard-working populace” were crucial to catch up with the West in a few decades. “The most startling discovery was how Christianity acted as a spiritual pillar holding up Western civilization. The mission members saw it as an ethical support and an encouragement to diligence. The resulting approach for the Japanese modernisation policy included Japanese spirit and Western learning, an approach that sought to capitalize on foreign technology without losing national identity. Other influential attitudes were “enrich the country, strengthen the military” and “increase production, promote industry” along Western lines with Shinto performing the same role as Christianity in the West”. In 1904-5, Japan defeated Russia, the 1st Asian country to defeat a modern European power, becoming one of the world’s leading powers by WW1.

Even countries like the UAE are recognising this as it reinvents itself as an AI center. Their AI Minister Omar Olama said “The only people in the world that banned it [the printing press] was the Arab Muslim empire— because of fear of the unknown. One decision led to the loss of every economic, scientific and cultural advancement."

So What About India?

It is evident that the 21st century promises profound changes and unparalleled opportunity in the world. The lessons for India are clear from the preceding paragraphs. India has always had the talent and market opportunity.

There is a need for a pervasive culture of innovation across sectors, within government, across society, and by individuals. It must encourage technology, commerce, mobility of people and ideas with confidence and agility. without ceding India’s ethos. The focus on artha followed bymoksha, of physics followed by metaphysics, on karma and jnana alongside bhakti, of “yuga dharma”, of adapting and adopting principles for changing times.

Modern laws, institutions, methods and modes of funding are fast falling into place. A new generation of confident, aware, mobile, uninhibited, skilled, capable and willing to “take on the world and win” Indians is rapidly emerging. There has never been a better time for Indians to uniquely recreate India as a brand that epitomizes riches, capacity, knowledge, and opportunity. This is one cultural battle India cannot afford to lose.

(Originally published at swarajyamag.com)