Trade - a ‘Sine qua non’ for India-US Relationship

The United States and India, the oldest and the largest democracies in the world, are collaborating more than ever before in promoting global security, stability, and economic prosperity through trade, investment, and sustainability initiatives. These natural allies with shared democratic values have strong people-to-people ties which is evident from the thriving four million-strong Indian American diaspora and a vibrantly ongoing educational exchange between the two countries. The United States and India have cooperated in dozens of bilateral dialogues and working groups, which span all aspects of human endeavour, from space and health cooperation to energy and high technology trade.

India’s potential for an expanded role in supporting secure supply chains for critical sectors came to the fore when supply chain vulnerabilities were exposed by COVID-19 and US-China trade frictions.The United States and India aim to cooperate on supply chain resilience, in particular, semiconductor supply chains.

India also seeks to partner with the United States to develop a secure pharmaceutical base; India is a major manufacturer and global supplier of generic drugs.

India is one of twelve countries partnering with the United States on the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) to make our economies more connected, resilient, clean, and democratic. The current Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity is an initiative to try to build regional cooperation on trade, supply chains and clean energy amongst like-minded countries. There are many complementarities that can be harnessed to build resilient global supply chains. While India has joined several of IPEF’s verticals such as supply chains, clean energy, infrastructure and decarbonisation, and tax and anticorruption, it has chosen to not join the trade pillar - given the sensitivities that need to be addressed.

In January 2023, the two nations also launched a bilateral initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET) to enhance cooperation on defence production, quantum computing, semiconductor supply chains, space, and other high-tech fields.

On March 10, 2023, US Commerce Secretary Ms Gina Raimondo and Indian Minister of Commerce and Industry Shri Piyush Goyal signed a US-India Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) that will establish a Semiconductor Supply Chain and Innovation Partnership. The MOU, announced at the relaunch of the US-India Commercial Dialogue, seeks to establish a collaborative mechanism between the two governments on semiconductor supply chain resilience and diversification in light of the US's CHIPS and Science Act and India's semiconductor Mission. The MoU envisages mutually beneficial research and development, talent and skill development.

Rapidly expanding trade and commercial linkages between India and the US form an important component of this multifaceted partnership between the two countries.

India’s largest trading partner

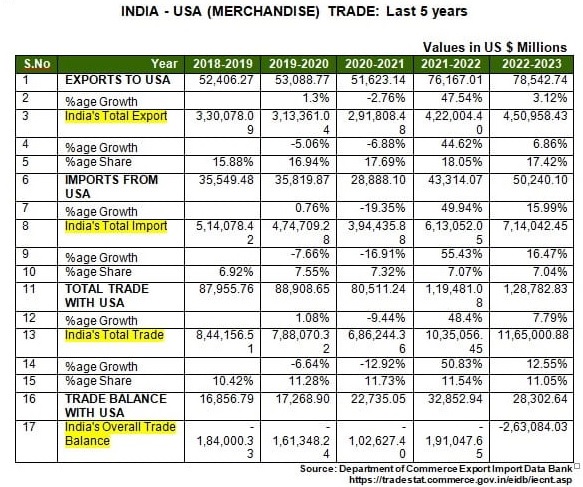

In 2022-23, overall US-India bilateral trade in goods reached a record $128 billion as compared to the earlier high of $ 119 billion in 2021-22. While the US is now India’s largest trading partner and also India’s biggest export market with a fifth of its exports going to the US, India on the other hand is the United States’ 9th largest market (with a 2.3% share). A snapshot of the India-US trade over the last 5 years is tabulated below:

In 2022, top US goods exported to India included oil and gas, miscellaneous manufactured commodities, coal and petroleum gases, basic chemicals, waste and scrap, and aerospace products and parts, while the top Indian goods exported to the US included miscellaneous manufactured commodities, pharmaceuticals and medicines, apparel, basic chemicals, textile furnishings, and petroleum and coal products. In services, travel was the top US export to India while various business services were top Indian exports to the US.

Barriers to realising the full trade potential

Even though India-US trade relations have strengthened over the last decade or so, they are far from being qualified as ne plus ultra.

Many issues have prevented harnessing of the full trade potential. While both nations are cautious about their current over-reliance on Chinese imports (both have substantial trade deficits with China), there are divergent views on tariffs, SPS standards on agriculture products, labour & environmental standards. Each sees the other’s agricultural support programs as market distorting.

The US has also expressed its concern on India’s data localization rules which it claims impacts American companies with cross-border data flows.

A key issue for India is US’s temporary VISA policies, which affect Indian nationals working in the US India continues to seek a ‘Totalisation Agreement’ to coordinate the social security protection for the key knowledge workers who split their careers between the two countries.

The United States also has longstanding concerns over India’s tariff rates, deeming them to be too high. Technically, India can raise its applied rates upto the bound rates without violating WTO commitments, however, US claims this causes uncertainty for the US exporters. India on the other hand opposes US “Section 232” tariffs on steel and aluminium (an additional 25% and 10%, respectively), initially applied in 2018. After being deprived of its GSP benefits, India applied retaliatory tariffs of an additional 10% to 25% on about $1.3 billion of US exports to India, namely, almonds, walnuts, apples, chemicals, and steel. The two sides have challenged these tariffs in the WTO. The United States rejected the 2022 WTO dispute panel ruling which concluded that its Section 232 measures are in violation of the WTO rules. Since then, the United States has negotiated less restrictive tariffs on their steel and aluminium imports with the European Union and some other trading partners, but not with India.

The investment scenario

USA is the 3rd largest investor in India, with cumulative FDI inflows of US$ 56,753 million from April 2000 to September 2022. The US is one of the most favoured destinations for Indian students for higher education. As per the annual Open Doors report issued in November 2022 almost 21% of total international students in the US are Indians. In 2022, around 82,000 student visas were issued in India, mostly for graduate and Masters programs. FDI from India in the United States is concentrated in the IT services, software, business services, pharmaceuticals, and industrial equipment sectors.

Many US companies view India as a critical market and have expanded their operations in India. Likewise, Indian companies seek to increase their presence in the US markets and at the end of 2020, Indian investment in the United States totalled US$ 12.7 billion, supporting over 70,000 American jobs. Nearly 200,000 Indian students in the United States contribute US$ 7.7 billion annually to the US economy.

Way forward

Despite the market access challenges, India continues to offer significant opportunities for US companies and the potential to increase bilateral trade is enormous Some large Indian conglomerates and high-tech companies are also the best in class when compared internationally and are increasing their footprint in the US significantly, contributing to the economy and creating jobs - more prominently so in IT and Pharma sectors.

US companies operating in India are also increasingly realising that success in India requires a long-term planning horizon and a state-by-state strategy to adapt to the complexity of India’s regional diversity.

Both countries want to boost their domestic manufacturing as one way forward. Be it the US’s “Made in America” program or India’s “Make in India” initiative. These goals, though commonly perceived as conflicting, are not exactly so – as both countries are at different stages of development and while India is largely focused on developing manufacturing and creating jobs in parts of the global supply chains, its focus is fundamentally different from the US’s focus on onshoring the high-end manufacture. Both sides can make progress here by improving market access for their respective manufactured goods.

The Joint Working Groups set up to address the trade and investment concerns need to be more focused on tackling the pain points in a time bound manner, not allow them to fester and cede concessions on a quid pro quo basis for the trade relationship to keep moving in the right direction.

The U.S.-India strategic partnership is founded on shared values including a commitment to democracy and upholding the rules-based international trading system. The United States and India have shared interests in promoting global security, stability, and economic prosperity through trade, investment, and connectivity.

The US will continue to be India’s largest export market in the foreseeable future - fuelling India’s economic growth, creating jobs and raising the domestic living standards while providing an access to affordable goods and services to the US.

(Exclusive to NatStrat)