Wular Lake. | ANI.

The stalled Tulbul Navigation Project deserves immediate revival, addressing Kashmir’s long-standing development needs after decades of diplomatic hesitation. This initiative would deliver crucial benefits in flood control and water management while alleviating downstream drainage issues. With Treaty constraints now suspended, India can pursue a more assertive water strategy, starting with the implementation of this shovel-ready project.

Introduction

On May 15, 2025, Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) Chief Minister Omar Abdullah raised an important question in his tweet regarding the Tulbul Navigation Project. Following the “temporary suspension”of the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), Mr. Abdullah inquired whether India could now resume work on this long-stalled project. The Chief Minister highlighted two significant potential benefits of completing the project, namely, enabling the use of the Jhelum River for navigation purposes and improving power generation capacity of downstream hydroelectric projects, particularly during the winter months when water levels are typically lower.

This development has reignited discussion about a project that many consider emblematic of the challenges in India-Pakistan relations.

The history of the Tulbul project stands as evidence of the difficulties in achieving peaceful resolution of bilateral issues with Pakistan, despite numerous diplomatic efforts by India over the decades. The renewed possibility of implementing this strategically important infrastructure project could mark a significant shift in regional water management and energy production capabilities for Jammu and Kashmir.

Background

The waterways of Kashmir have historically served as vital arteries for transportation and commerce. During the pre-Independence era, approximately 70% of total cargo in the Kashmir Valley was transported via large boats locally known as ‘khachus’,with payload capacities reaching 15 tonnes.

The unprecedented boom in Kashmir’s horticulture sector post independence, particularly in Sopore and adjacent areas led to significantly increased freight volumes. This situation necessitated alternative, more economical river transport systems with mechanised river transport services replacing traditional khachuspropelled by manual oar power. This would also reduce road congestion and environmental pollution caused by truck exhaust emissions in areas surrounding the Jhelum River.

Geographical Context: The Jhelum River and Wular Lake System

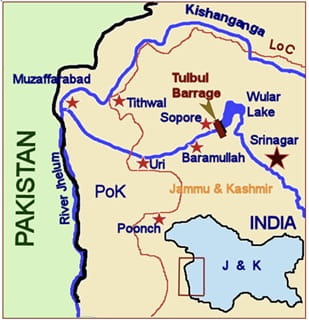

The Jhelum River constitutes the sole natural waterway in the Kashmir Valley with viable potential for inland navigation development. The river originates from a spring at Varinagh on the southeastern periphery of the Kashmir Valley. It enters the plains at Khanabal and subsequently flows through numerous significant population centers including Anantnag and Srinagar before emptying into Wular Lake at Baniyari. The Wular Lake extends to Ningli, where an outfall channel continues toward Baramulla. The river follows a gentle gradient between Khanabal and Baramulla—a distance of approximately 170 kilometers—rendering this stretch particularly suitable for navigation purposes.

Wular Lake receives multiple inflows (Jhelum River, Madhumati Nallah, Arin Popehin, Ningli, other tributaries) but has only one outlet through the Jhelum River at Ningli. Historically, the lake maintained highest natural levels around 5200 feet and ensured year-round navigation with sustained discharge.

In the 1960s, to address flooding in Sopore and nearby areas, authorities dredged 20 kilometersof the river channel from Ningli to Baramulla. While this action helped in reduced flooding, it created an unintended consequence: a premature depletion of the lake in the winter and consequent reduced winter discharge. This ledto insufficient depth for commercial navigation between October and February and eliminated year-round navigation capability in the system.

The Tulbul Navigation Project: Concept and Design

The Tulbul Navigation Project was conceived and initiated by the Government of Jammu and Kashmir in 1984 to address two interconnected challenges: establishing year-round navigation capabilities and providing enhanced flood protection during monsoon periods. Situated on the Jhelum River immediately downstream of Wular Lake, the project aimed specifically to improve navigability along the critical 20-kilometer stretch between Wular Lake and Baramulla, thus facilitating continuous transportation and tourism operations throughout the year.

The proposed site of the Tulbul Navigation Project

The project design incorporates the utilisation of the natural storage capacity of the Wular Lake to augment the flows in the Jhelum downstream of Wular lake through controlled water releases during winter months (November through February) when natural water levels are insufficient for navigation.

The project’s operational protocols allow the Wular Lake to fill naturally to its seasonal maximum level. Once the lake starts depleting, the regulatory intervention through active gate management would commence and would maintain the controlled release to ensure the required navigable depth throughout the year. Additionally, this regulated flow would enhance power generation efficiency at hydroelectric installations downstream, benefiting both Indian and Pakistani facilities.

Project History and the Context of the Indus Waters Treaty

The Tulbul Navigation Project received technical clearance from India’s Ministry of Shipping and Transport in November 1981, with an estimated implementation cost of Rs. 30 crores. Construction activities commenced in 1984 under the direction of Jammu and Kashmir’s Tourism/Transport Department. However, in March 1985, Pakistan raised formal objections to the design of this project on the pretext that it violates the Indus Waters Treaty. The initial prolonged bilateral discussions within the Permanent Indus Commission did not yield any headway and the matter was escalated to the Secretary level. Pakistan demanded the immediate stoppage of work as a precondition to begin negotiations at the Secretary level.

As a goodwill measure to facilitate productive dialogue, India suspended project construction in September 1987 for an initial three-month period. Following two rounds of Secretary-level talks, India agreed to an additional three-month suspension and subsequently granted two one-month extensions of the work suspension through June 2, 1988. During this period, five rounds of Secretary-level negotiations took place but remained without a conclusive resolution. After the fifth round, India agreed to Pakistan’s request of an indefinite suspension until an amicable settlement could be reached.

In totality, the matter had been discussed in six meetings of Permanent Indus Commission (May 1986 to July 1987) in eight rounds of Secretary-level talks from 1987 to 1992 and in six more rounds at Secretary-level under composite dialogue (November 1998 to March 2012), a fair indication of Pakistan’s intent of dragging the issue to ensure the work remains suspended.

Legal Positions of Both Countries

Pakistan’s primary argument references Article I (4) to contend that the Wular Lake constitutes an integral component of the Jhelum River itself, thereby subjecting it to all restrictions applicable to the river proper. Pakistan further characterises the Tulbul Navigation Project as a barrage that violates the 10,000 acre-feet limit of storage capacity incidental to a barrage on the Jhelum Main, imposed by the Treaty under Article III (4) read with Paragraph 8 (h) of Annexure E.

India maintains that the project fully complies with the Treaty provisions, specifically referencing Article I (11) which explicitly permits navigation development. India emphasises that the project utilises only the natural storage capacity already present in the Wular Lake for navigation purposes—classified as “non-consumptive use” under the Treaty definitions. The Indian position holds that the infrastructure merely regulates outflow of the lake’s natural storage rather than creating new impoundment capacity. India contends that the project does not constitute a storage work as defined by the Treaty and has comprehensively demonstrated the project’s full compliance with Treaty provisions.

Strategic Assessment of India’s Position

India’s primary strength lies in Pakistan’s inability to demonstrate tangible harm resulting from the project’s implementation.

Pakistan’s objections remain principally theoretical, based on isolated interpretations of specific Treaty provisions without consideration of broader context or practical impacts. In contrast, the Treaty’s preamble explicitly articulates its overarching purpose as facilitating “the most complete and satisfactory utilization of the waters of the Indus system of rivers.” The Pakistani position effectively advocates for an interpretation that mandates rapid depletion of Wular Lake waters without benefiting any stakeholders, while simultaneously causing significant navigational impediments on the Jhelum River.

Experts believe Pakistan’s objections stem from a deep-rooted apprehension that this project has the capability to damage its Triple-Canal project. The Triple-Canal Project was a major irrigation initiative in British India’s Punjab region, completed in 1917. It consisted of three interconnected canals (Upper Jhelum, Upper Chenab and Lower Bari Doab) that transferred water between rivers to irrigate extensive agricultural lands, significantly improving agriculture and economic productivity in the region.

Pakistani experts also highlight that the storage behind the Wullar Barrage is estimated as 0.324 MAF, which is about 32 times the storage of 0.01 MAF incidental to a barrage permitted by the Treaty. In a nutshell, Pakistan apprehends that India shall have control over 0.324 MAF of water which is more than 20 times of storage of Kishenganga and thrice of Pakal Dul, and the same might be used as a weapon of war, if India so decides.

Implications of the Suspension

The project has remained suspended since October 2, 1987 and has continued without a formal end date. This indefinite suspension effectively helps Pakistan in achieving the goal of stalling infrastructure projects in J&K.

The financial implications are substantial. Continued suspension generates multiple detrimental outcomes: local populations are denied anticipated benefits in navigation, fisheries, tourism and related economic activities; existing structures deteriorate while project costs continue escalating.

Way Forward for India: It’s Now or Never

India’s original work suspension constituted a voluntary goodwill gesture. The Indus Waters Treaty contains no provision requiring suspension of work undertaken by India on the Western rivers. With the Treaty in abeyance now, India is not bound by the restrictions imposed by the Treaty on her works onthe Western rivers and not even obligated to provide project data to Pakistan. The work can be completed in fourworking seasons.

The Tulbul Navigation Project would revitalise regional transportation by enabling cost-effective bulk cargo movement via modernised watercraft, reducing road congestion while particularly benefitting the agricultural and horticultural sectors. The project would stimulate tourism along the Jhelum waterway, creating economic opportunities for riverside communities.

It would also improve flood management for vulnerable areas like Sopore while maintaining sufficient water depths year-round for navigation. Additionally, regulated water flow would enhance downstream hydroelectric power generation efficiency and will help firm up power generation in downstream hydroelectric projectsin India to the tune of 192.1 GWh. The indefinite construction suspension has prevented realisation of the above advantages for decades.

Conclusion

The Tulbul Navigation Project represents a significant initiative to modernise and revitalise traditional water transportation systems in Kashmir while addressing flood management challenges. Its innovative design utilises natural lake storage through flow regulation rather than creating new impoundment structures, making it compatible with sustainable water resource management principles.

The Tulbul Navigation Project, if implemented, could serve as a model for balanced development of water resources that preserves traditional livelihood systems while enhancing their economic viability through appropriate technological modernization. This approach aligns with broader sustainable development goals for the region while honoring its cultural and historical relationship with its waterways.

The stalled Tulbul Navigation Project deserves immediate revival, addressing Kashmir’s long-standing development needs after decades of diplomatic hesitation. This initiative would deliver crucial benefits in flood control and water management while alleviating downstream drainage issues. With Treaty constraints now suspended, India can pursue a more assertive water strategy, starting with the implementation of this shovel-ready project.

(Exclusive to NatStrat)