Representative image. | Finance Saathi.

It is well understood that state-level incentives are independent of the Centre’s incentives and that industry players are free to establish operations in the state of their choice. Prime Minister Modi also called for “engage in healthy competition with one another to build semiconductor ecosystems and enhance the investment climate within their regions”.

Introduction

Indian states actively engage in a competitive landscape to attract semiconductor investments, recognising the sector’s transformative potential to reshape their industrial landscapes and generate high-quality employment opportunities.

Semiconductor is a new buzzword in the geopolitical contest between the great powers, which was recently weaponised by the American President Donald Trump, and thenby the Chinese, to control the highly sophisticated technology in the world.

In this great power competition, aspiring global powers such as India have a sweet spot to attract global semiconductor companies to establish their fab units and jointly manufacture chips on Indian territory.India’s journey to the semiconductor industry, which began in the mid-1980s, has had its ups and downs, and is now entering the maturing phase, creating its own manufacturing ecosystem. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has accelerated the semiconductor manufacturing ecosystem in the post-COVID period through massive investments and joint-venture Memoranda of Understanding (MoU) signed between Indian companies and global players. During the SEMICON India 2025, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said, “Our journey is late, but nothing can stop us now…India is now moving from backbend to becoming a full-stack semiconductor nation. The day is not far when India's smallest chip will drive the world's biggest change... the day is not far when the whole world will say - designed by India, made in India, Trusted by the world.”

In total, there have been ten semiconductor projects worth approximately $18 billion (more than ₹1,59,00 crores) in investment commitments and over $7 billion (nearly ₹62,000 crores) in subsidies allocated since the Prime Minister initiated the expansion of its manufacturing fabs. In addition to this, 23 chip design projects have been sanctioned, a new technical curriculum has been designed, and over 60,000 students or trainees have participated in the training programs organised by the government.

The entire fab ecosystem has expanded and transformed from a virtually non-existent presence to a massive, multi-project initiative with ten projects in the last four years. India recently announced ventures for a compound fab and advanced electronic packaging. Under these projects, chips will be manufactured, assembled, and packaged primarily within the 28-110 nm range, which will be beneficial in various everyday applications, including consumer products, electronics, the automotive sector, computing, data storage, and wireless communications.

The target is to manufacture and sell it in the domestic market, as well as export it globally. According to Fortune Business Insights(2025), “The global semiconductor market size was valued at over $681 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow from over $755 billion in 2025 to more than $2,062 billion by 2032, exhibiting a CAGR of 15.4% during the forecast period (2025-2032)”.

However, India’s efforts to create a chip manufacturing ecosystem have seen ups and downs in its 40-year history. For instance, in its semiconductor journey, in 1984, it established the Semiconductor Complex Limited (SCL) in Chandigarh, securing licensing agreements from Hitachi, AMI, and Rockwell. In 1985, Metkem Silicon Ltd., supported by BEL, set up polysilicon facilities in Mettur, Tamil Nadu. In 1989, a fire at SCL severely damaged the Chandigarh facility, affecting its output for ISRO and other projects. Then, in March 2007, India announced its first Semiconductor Policy, targeting ₹24,000 crore in investment and the establishment of three semiconductor fabrication facilities. All these efforts failed due to policy failures and the government's lacklustre behaviour in these sectors.

The great power competition in the technological domain, particularly between the US and China, which began in the mid-to-late 2010s, has created vulnerabilities in the global market for high-technology sectors. This is exemplified by the Trump-led 2019 restrictions on American chips to China and the pressure on ASML not to export to China. The COVID-19 disruptions in the global chip supply chain and related risks convinced the Modi government to invest heavily in this sector, including a 70 per cent capital subsidy for Micron to build a semiconductor assembly and testing plant in Sanand, Gujarat. The central subsidy of 25 per cent offered by the UPA and the Modi government until 2021 was doubled under the India Semiconductor Mission. It was this increased subsidy, plus rising domestic demand, that made the difference. This initiative has progressed successfully, without significant setbacks. India’s chip market is expected to boom, reaching $100–110 billion by 2030.

From Idea to Implementation

In December 2021, the Indian Semiconductor Mission (ISM) was established as the national authority under the Central Government’s Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) to evaluate and assess investments, as well as implement semiconductor initiatives within the country. The ISM has approved ten projects to strengthen India’s semiconductor ecosystem in under four years. These projects encompass a range of investments, from the substantial $11 billion (₹91,000 crores) fab investment announced by Tata Electronics Private Limited with the Partnership of Taiwan’s Powerchip Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (PSMC) to the cumulative investment of over $2.75 billion from Micron Technology in establishing an assembly, testing, marking, and packaging (ATMP) facility. Other significant projects include an outsourced semiconductor assembly and test (OSAT) plant in Assam, two manufacturing facilities in Sanand, Gujarat, and a semiconductor plant in Uttar Pradesh.

The government’s Semicon India programme, launched with a budget of ₹76,000 crore ($9.2 billion), aims to support not only fab manufacturing units but also the entire chip production ecosystem. From 2023 to 2025, a total of ten approved projects under ISM were reached, with cumulative investments of around ₹1.62 lakh crore ($19.3 billion) in six states.

More recent approvals were in Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, and Punjab, which have increased total investments to $18.3 billion. The programme offers production-linked incentives to encourage domestic production of electronic components and semiconductor manufacturing. Major names are already on board, with Tata Electronics in Gujarat and Assam; Foxconn and HCL Group in Jewar; CG Power-Renesas in Gujarat; and Micron’s assembly, test, manufacturing and packaging facility in Gujarat. Prime Minister Modi has pledged that India-made chips will be commercially available by the end of 2025.

On 12 August 2025, the Union Cabinet, chaired by Prime Minister Modi, approved the establishment of our new semiconductor manufacturing facilities under the ISM. This marked a significant step towards strengthening India’s semiconductor ecosystem. The approved proposals from SiCSem, Continental Device India Private Limited (CDIL), 3D Glass Solutions Inc., and Advanced System in Package (ASIP) Technologies will attract a combined investment of around ₹4,600 crore and are expected to generate employment for more than 2,000 skilled professionals. With these approvals, the total number of sanctioned projects under ISM now stands at ten, spanning six states with cumulative investments of approximately ₹1.60 lakh crore. These new facilities, including India’s first commercial compound semiconductor fab by SiCSem and a cutting-edge glass substrate packaging unit by 3DGS, both in Odisha, are poised to play a critical role in advancing technologies for defence, EVs, telecom, AI, and consumer electronics, contributing significantly to the vision of an Atmanirbhar and Viksit Bharat (see Table 1).

Table 1. India’s Semiconductor Facilities

Source: India’s Semiconductor Revolution Powering the Future of Electronics and Bloomberg

Indian States are Competing

Indian states actively engage in a competitive landscape to attract semiconductor investments, recognising the sector’s transformative potential to reshape their industrial landscapes and generate high-quality employment opportunities.

The High Commission of Singapore in India visits the TSAT plant in Assam. | X: @SGinIndia.

The Tata Semiconductor Assembly and Test (TSAT) plant in Assam is a good example of a state’s proactive approach to attracting semiconductor investments. Despite Assam not being a conventional destination for such investments or possessing the most favourable financial incentive scheme, TSAT made a significant investment in the state. And this is a positive sign in the formative phase of the semiconductor industry in India. Gujarat has also emerged as a leading contender, not solely due to the support of the Central Government but also through strategic initiatives and comprehensive infrastructure planning. Gujarat is the first Indian state with a dedicated Semiconductor policy (Gujarat Semiconductor Policy (2022-2027)with the fiscal support of the policy. The policy incentivises 40 per cent of the CAPEX assistance approved by the India Government under national schemes for Semiconductors and Display Fab Ecosystem. This focused approach by Gujarat distinguished it from states like Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, whose policies were more broadly aimed at the electronics sector. Gujarat’s early and specific commitment conferred it a crucial first-mover advantage.

Furthermore, the development of the Dholera Special Investment Region (Dholera SIR), a 900-square-kilometre industrial city, has propelled Gujarat ahead of its competitors. In contrast to the retrofitted brownfield clusters in Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh, which are designed for electronics and automotive manufacturing, Dholera SIR is a greenfield development dedicated to the semiconductor industry. Its proximity to two major ports further enhances its appeal by facilitating efficient logistics and exports.

Micron Technology’s landmark investment in Gujarat in 2023 played a critical role in validating the state’s semiconductor ecosystem. Although heavily subsidised by the central and state governments, Micron’s entry acted as a catalyst, establishing a network of suppliers and sub-suppliers and conveying to the global industry that India and Gujarat are exceptionally prepared for semiconductor manufacturing.

However, Gujarat’s success cannot be solely attributed to financial incentives. Other states, such as Uttar Pradesh, have offered significantly more generous subsidies, including complete reimbursement of project costs, yet have failed to attract substantial investments. Even Karnataka could not materialise its plans despite an early memorandum of understanding with a semiconductor consortium in 2022.

Gujarat’s relative success lies in combining moderate but adequate financial support with speedy project execution and strategic infrastructure development. This suggests that while incentive packages are essential, they must be complemented by focused policy frameworks, cluster-based infrastructure, and swift administrative execution to make a state truly competitive in the global semiconductor race.

Proliferation of Data Centres

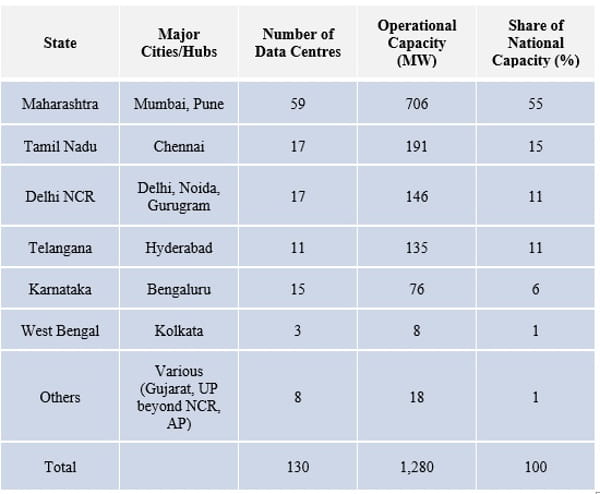

With the chip manufacturing ecosystem, India is also expanding its footprint in the data centre proliferation. India is among the major powers that are massively investing in the creation of data centres. According to recent data, by the end of the first half of 2025, the total operational centre capacity stands at around 1,280 MW, which saw a massive jump from 722 MW in 2022. The total number of operational data centres is estimated to be 130 by the end of the first half of 2025, representing a 50 per cent jump from its 2022 tally.

The Central Government, in association with state-level governments, is working to create an ecosystem for data centres. The 2025 Union budget allocated approximately ₹1,900 crore to build the entire ecosystem of data centres and cybersecurity. It proposes tax holidays (for example, 15 per cent concessional rates), investment allowances for Tier-II cities, and a reduction in customs duty on Carrier Grade Ethernet Switches (from 20 per cent to 10 per cent) to lower telecom infrastructure costs.

Through land subsidies, stamp duty waivers, electricity tariff concessions, and single-window clearances, the state government offers flexible policies to facilitate the construction of data centres within its state. Southern states like Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and Karnataka, as well as Western states like Maharashtra and Gujarat, and Northern states like Delhi and Uttar Pradesh, provide these incentives. Maharashtra’s IT & ITES Policy 2023, for instance, provides flexible policies to use land for the data centres, and also offers property tax at residential rates. These regulations boost the confidence of investors, reduce operational costs, and promote positioning India as a global data centre hub.

Source: Vidit J. State-Wise Growth and Distribution of Data Centres in India: A 2025 Perspective

Challenges and Conclusion

There are five broad challenges in India’s semiconductor journey. First, India lacks the infrastructure and reliable supply chains for essential materials such as ultrapure chemicals, speciality gases, and silicon wafers, which poses a significant hurdle. Second, we have a limited pool of skilled labour trained specifically for chip manufacturing. The government should invest in vocational training in colleges or short-term training for the semi-skilled workforce. Third, a lack of high capital investment, especially from the private sector, for setting up fabs, and government subsidy schemes may deter private investors from seeking sustained government support. Fourth, the absence of a strong semiconductor design and intellectual property ecosystem makes India heavily reliant on foreign players. Finally, the supply chain is vulnerable amid the US-led technological containment of rising powers, which is compounded by geopolitical uncertainties and dependence on imported machinery and materials from a few countries.

The government's formative efforts are commendable in establishing a self-reliant semiconductor ecosystem that necessitates consistent policy support, private sector activism, strategic collaborations with global partners, and a focused development strategy aimed at nurturing technical expertise and optimising supply chains.

(Exclusive to NatStrat)