India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi with ASEAN leaders at the 20th ASEAN-India Summit, Jakarta, on September 07, 2023.

Apart from consolidating the support for Chinese Government’s regime legitimacy, the idea of ‘neighborhood community’ also reflects a socialisation process where China has a leadership role and positions itself as a lynchpin against external pressures in the region. This undermines the idea of ‘centrality of ASEAN’ in regional issues.

Introduction

Southeast Asia has long been a region of strategic importance for India, especially the countries in the lower Mekong region along with the other Association for South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states. However, recent developments have shown cracks within this seemingly united bloc, driven by internal rifts, territorial conflicts and the growing influence of China. For India, which has strategically focused on strengthening ties with ASEAN through its “Act East” policy, these shifts pose significant challenges, particularly in the context of Myanmar's crisis, escalating tensions between Cambodia and Thailand and China's deepening presence in the region through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Myanmar Situation

The civil war in Myanmar has been one of the most destabilising factors in Southeast Asia in recent years following the February 2021 military coup that ousted the democratically-elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi, plunging the country into a brutal civil conflict. This internal strife has not only caused a humanitarian crisis but also impacted India’s internal security concerns in northeastern states where Manipur has suffered in recent months.

India’s security concerns are exacerbated through the inflow of refugees, militants, drug trafficking and illegal trade from Myanmar. India has had to reassess its border security policies, including tightening border controls and scrapping the free movement regime with Myanmar. Meanwhile, Myanmar has emerged as the biggest source of rare earth elements (REEs) exports to China, accounting for more than half of China’s import of REEs. Since the 2021 military coup, the REEs export from Myanmar to China has increased five times to $3.6 billion.

Between January 2017 to December 2024, Myanmar exported over 290,000 tonnes of REEs to China, out of which over 170,000 tonnes were exported after the 2021 coup. These exports from Myanmar further strengthen China’s monopoly over the REEs supply chains. The unregulated rare earths mining in Myanmar, most of which is near the China border, is directed by the Chinese enterprises. It is now poisoning the rivers flowing into Thailand and could soon lead to issues between Myanmar and Thailand.

Cambodia-Thailand Tensions

Cambodia-Thailand ties have undergone significant changes in recent years, often influenced by the complex interaction of domestic politics, economic interests and historical antagonisms. Past conflicts such as the 2008 Preah Vihear Temple dispute have traditionally been at the forefront of Cambodia-Thailand relations. Following the resolution of this issue, the bilateral focus shifted to the overlapping maritime claims in the Gulf of Thailand: an area potentially rich in natural gas resources.

In May 2025, the tensions along the disputed Cambodia-Thailand border escalated into a crisis following a brief military clash. Tensions erupted again in July 2025 with casualties and displaced people on both sides. This long-standing territorial dispute remains a potential flashpoint, particularly if bilateral negotiations are undermined by rising nationalism and poor management of ties on both sides. This conflict poses a significant challenge to ASEAN’s unity, allowing external actors to take advantage of divisions within ASEAN.

BRI’s Regional Footprint

Among the lower Mekong countries, Laos and Cambodia have fully embraced the BRI, Vietnam has been cautious while Thailand and Myanmar have adopted some major BRI projects but there are issues in their implementation. Beijing has long supported the Myanmar military junta through arms supplies, economic investments through the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) and diplomatic support. The Muse–Mandalay railway and Kyaukphyu deep seaport are key projects of CMEC under the BRI which provide China access to the Indian Ocean via the Bay of Bengal.

Similarly, Cambodia enjoys a close relationship with China. The ruling elites and the private sector in Cambodia see China’s BRI as an opportunity for their country to become a high-income country by 2050. China and Cambodia are jointly funding the construction of $1.2 billion Funan Techo Canal in Cambodia that will connect the capital, Phnom Penh, to the Southern coast of the country giving it access to the Gulf of Thailand.

For Vietnam, this canal is an economic and environmental threat. There is a possibility that water flow to Vietnam’s Mekong Delta could decrease, impacting food security of millions of people in the country. The Secretariat of the intergovernmental Mekong River Commission (MRC) that coordinates the sustainable development of Southeast Asia's longest river asked Cambodia to share a feasibility study on the impact of the China-backed canal so that the broader impact on the Mekong region is considered before implementing the project.

China is also involved in building a section of Cambodia’s Ream naval base from 2020. Experts have highlighted that the new canal and the naval base will allow China to monitor critical shipping lanes via the Strait of Malacca through which the majority of China’s trade and energy flows. Cambodia has pursued a closer strategic relationship with China in order to balance Thailand and Vietnam. This canal will reduce Cambodia’s reliance on Vietnam and increase China’s leverage with Vietnam with whom it has a maritime dispute.

Implications for India and ASEAN

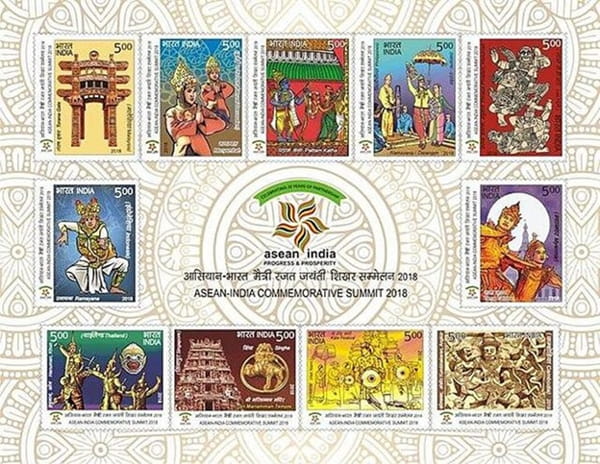

Commemorative stamps showing glimpses of Ramayana from different ASEAN countries.

The developments highlighted above complicate India’s efforts to strengthen the ASEAN bloc as New Delhi supports a strong and unified ASEAN. Growing dependencies of countries like Myanmar and Cambodia on China complicate regional dynamics and exacerbate divisions within ASEAN, limiting India’s ability to counter Beijing’s expanding influence in Southeast Asia, especially in areas such as maritime security and regional cooperation including issues in the South China Sea (SCS).

One of the major challenges for ASEAN, particularly regarding the SCS, is the differing viewpoints, claims and positions among its member states. These differences make it difficult for ASEAN to present a unified stance on key regional issues, especially in negotiating the Code of Conduct in the SCS.

Vietnam and the Philippines, which have frequent confrontations with China in the SCS over territory, want a binding Code of Conduct but others like Laos and Cambodia, which are aligned with China, have been cautious about any binding agreement. Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos face challenges in opposing China’s policies without damaging their bilateral ties with Beijing, further complicating efforts to achieve consensus within the ASEAN.

In 2013, China had proposed strengthening its relationship with ASEAN through the concept of “China-ASEAN Community with a Shared Future” while in 2021, the two sides announced a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership. Beijing has been emphasising the concept of ‘neighborhood community’ to build economic interdependence with its neighboring countries.

Apart from consolidating the support for Chinese Government’s regime legitimacy, the idea of ‘neighborhood community’ also reflects a socialisation process where China has a leadership role and positions itself as a lynchpin against external pressures in the region. This undermines the idea of ‘centrality of ASEAN’ in the regional issues.

At the same time, it provides China a bigger canvas in the Mekong region to push its own economic and strategic concerns at the expense of the regional countries. This could strengthen China’s strategic footprint in the Bay of Bengal and undermine the idea of the Indo-Pacific by complicating the balance of power considerations in the region.

Conclusion

India’s ‘Act East’ policy completed a decade in 2024. In the following decade, New Delhi should put more focus and diplomatic energy in its ties with the Mekong countries. To begin with, more proactive posturing at the Mekong-Ganga Cooperation (MGC) will help regional countries in counterbalancing their dependence on China, thus contributing to regional stability.

With like-minded countries, India should also have an eye on developments in Myanmar so that China is not allowed to totally influence the country. India should further deepen its ties with Vietnam and the two sides should explore cooperation over REEs as Vietnam ranks third in the world in terms of its rare earth mining potential. Vietnam has the political will and desire to geopolitically balance China including its dominance of the REEs supply chains. Beijing’s growing economic and military footprint in the lower Mekong region also calls for India’s reenergised focus to upgrade the military infrastructure at the strategically located Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

(Exclusive to NatStrat)