Representative image. | DC Studio on FreePik.

The Strategic Imperative of Cyber Deterrence

In this modern era, there is a tremendous transformation that the security architecture of South Asia is undergoing that is driven by digital space weaponisation. For India, which is currently located in one of the world’s most volatile geopolitical neighborhoods, the challenges that it is facing as a rising power is existential. As a nation, India is sandwiched between two nuclear-armed adversaries, that is, Pakistan and China - both of whom possess distinct and evolving offensive cyber capabilities. This places India in the ‘grey-zone’ of cyberspace where as a country it should face a ‘two-front war’ scenario that is no longer theoretical but active as well. This article presents a detailed and exhaustive analysis of India’s cyber deterrence posture where the focus has been on evaluating the credibility of the threats it faces, the infrastructure resilience it maintains and the systemic constraints that currently inhibits the projection of effective cyber power.

This research attempts to address if India can credibly deter state and non-state cyber adversaries given its current institutional, doctrinal, and capability constraints effectively? Based on the current trend, it is evident that while India is transitioning from a passive to an active defence posture, as a country it suffers from “credibility gaps” that are driven by fragmentation at institutional levels, and the absence of a declared punishable doctrine, and significant asymmetries in offensive cyber capabilities relative to China.

Theoretical Framework: Denial and Punishment in the Digital Age

The deterrence theory states that an adversary can be dissuaded from aggression primarily through two essential mechanisms: deterrence by denial and deterrence by punishment [1]

● Deterrence by Denialis defined by how well either an individual or an entity takes necessary steps to harden defences to the extent that an attack (kinetic or non-kinetic or cyber) is perceived as ineffective or inefficacious and expensive in terms of resources, bandwidth, and time relative to the expected gain. In association with cyberspace, this defines how well an entity (enterprise, organisation, an individual or a nation) has defenses in place that are equivalent to robust resilience, redundancy and defensive depth. Example: ensuring that even if a firewall is breached, the threat actor is unable to achieve the strategic objective (for example, data exfiltration or complete network/infrastructure encryption) [3].

● Deterrence by Punishmentis defined as how well an entity retaliates to a threat. It necessitates that the deterrer have both the demonstrated political will and the ability to do exceptional or intolerable harm (whether in the cyber domain or through cross-domain escalation). It must also have the ability and expertise to conduct threat actor attributions: the capacity to positively identify the aggressor (be it a state-sponsored actor, an Advanced Persistent Threat Group or a mere hacktivist) [2].

From a cyber intelligence and cyber warfare perspective, these classical models have certain complications. One of them is the “attribution problem” where threat actors actively leverage open-source proxies to maintain anonymity while conducting cyber attacks to eventually erode the certainty of punishment and to remain unattributed [4]while law enforcement and regulatory bodies struggle to be able to attribute the threat to an individual, group or a nation. The idea of "escalation dominance" is slightly ambiguous because in contrast to a nuclear missile, a cyber weapon (exploit) is ideally "single-use" once it is deployed until the vulnerability is patched and the exploit becomes outdated [6]. Therefore, security researchers and scholars contend that cyber deterrence is more difficult to maintain and communicate than traditional deterrence [2].

The Indian Context: A Unique Vulnerability

Today, India is rapidly digitising its economy from becoming a global IT hub to rolling out massive Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) such as Unified Payments Interface (UPI) and Aadhar.

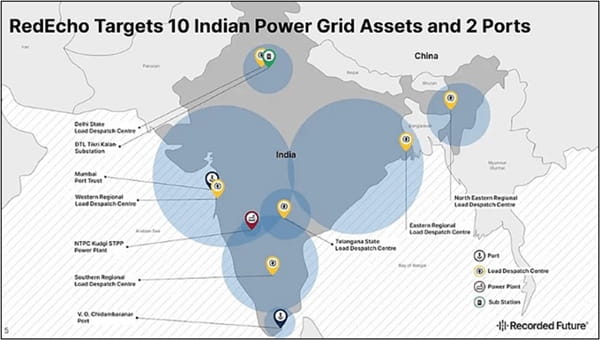

However, it is important to note that its offensive and defensive cyber doctrines have significantly lagged behind its technological adoption and this warrants focused analysis due to its “Strategic Asymmetry” [7]. India today is realistically dealing with “tyranny of geography” combined with “tyranny of connectivity”. While India’s critical infrastructure such as banking, power, transportation are becoming more interconnected with each other and with other essential services, the attack surface is also equally becoming more accessible for threat actors to exploit. A notable threat actor in this regard is the Chinese state-sponsored group “RedEcho”, other state-sponsored groups from Pakistan and hacktivists from Bangladesh [9].

The Adversarial Landscape: A Spectrum of Threats

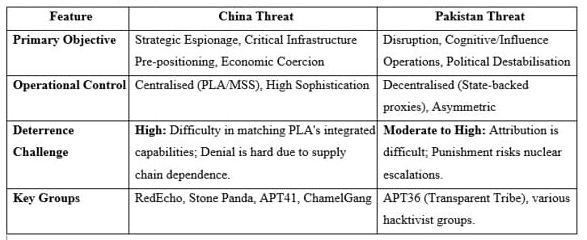

In order to effectively evaluate deterrence, one must first understand who is being deterred. China and Pakistan are part of India’s “three-body” strategic architecture, where each poses a unique deterrence threat [11].

The China Challenge: System-of-Systems Warfare

India’s “pacing threat” in cyberspace predominantly is China followed by Pakistan. In order to incorporate cyber, space and electronic warfare capabilities, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has undergone significant institutional changes.

● Strategic Support Force (SSF) and Beyond: Up until recently, China’s information warfare capabilities were consolidated under the strategic support force (SSF). This was further refined into specialist wings, such as the “Information Support force” [12], during a recent reform in 2024. China is able to carry out “System-of-Systems” warfare, which aims to deafen and blind an enemy’s command and control (C2) networks, because of this integration [13].

● Civil-Military Fusion: A vast ecosystem of civilian hackers and state-affiliated/sponsored groups augment the Chinese cyber power such as APT41, RedEcho who regularly are tasked to conduct espionage and pre-positioning attacks on the Indian infrastructure [9]. According to “The China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI)”, People’s Liberation Army (PLA) views cyber capabilities as a means to “win without fighting” by ensuring that the will of the enemy and their respective infrastructure is degraded before kinetic hostilities initiate [13].

● Grey-Zone Tactics: China believes and executes what is called the “Salami Slicing” in cyberspace where they conduct low-intensity, persistent intrusions like the 2020 Mumbai power outage or probing into the Indian rail network infrastructure that ideally fall under the threshold of “armed conflict/attack” thereby rendering India’s conventional deterrence threats irrelevant [3].

The Pakistan Challenge: Asymmetric and Cognitive Warfare

From a technological advancement perspective, Pakistan is known to possess fewer indigenous resources compared to India or China and hence employ asymmetric strategy in their cyber operations.

● Cognitive Warfare: “Fifth-Generation Warfare (5GW)” and “Cyber enabled Influence Operations” are two focus areas that Pakistan follows as part of their doctrine. The same was witnessed at the time of Operation Sindhoor where Pakistani hacktivists groups actively engaged in spreading disinformation and influence operations campaigns against India [17]. Further threat actor groups such as APT36 aka Transparent Tribe regularly conducts sophisticated cyber attacks against India targeting mostly defence personnel and Government organisations.

● Proxy Dynamics: Pakistan maintains “plausible deniability” by also leveraging non-state actors and hacktivist groups. Indian security researchers note that even low-level cyber harassment can escalate quickly during a crisis, as seen in the post Operation Sindhoor and post-pulwama disinformation campaigns [18].

Comparative Threat Matrix

Doctrinal Clarity and Strategic Signalling

For any country, the deterrence strategy they develop should require clear “hard line” boundaries which, if crossed, will be responded with a guaranteed retaliation [2]. Though recent events suggest a change, India's theological stance has traditionally been marked by reticence/reserve.

The Void: National Cyber Security Policy (2013) Strategy (2020-2025)

Bharat National Cyber Security Exercise (NCX) 2023, New Delhi. | National Security Council Secretariat of India.

The National Cyber Security Policy (NCSP) of 2013 is still India's sole official public document. Most people consider this document to be out of date [19]. It places a lot of emphasis on capacity creation and "resilience" (deterrence via denial) but it does not provide operational information about how India uses cyber capabilities for statecraft or retaliation because in my opinion, it is more of a policy framework [20]. In 2020, a comprehensive National Cyber Security Strategy (NCSS) was drafted to replace the 2013 policy. However, as of early 2026, this updated policy document remains unreleased [21]. Scholars are likely considering this delay due to "bureaucratic turf conflicts” between the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY), the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) and the National Security Council Secretariat (NSCS). However, there is no definitive official confirmation that the delay is solely because of turf wars. Other plausible causes include: the complexity of updating a national strategy in response to rapidly evolving cyber threats, need for inter-ministerial consultations, legal and policy review cycles, and internal approval processes. Therefore, while bureaucratic friction is a credible explanatory factor, it should be characterised in research as one plausible interpretation rather than an uncontested official fact.

Now, due to this, we should anticipate that “strategic ambiguity” might be created in the absence of such a definitive strategy. From an angle, such ambiguity can theoretically enhance deterrence by keeping adversaries uncertain, usually it will be interpreted as India’s indecision or incapacity [19]- this risk continues to be there unless India acts on this strategic ambiguity. If India does not have a declared policy on Offensive Cyber Operations (OCO), threat actors and other state-sponsored adversaries may calculate that sub-threshold attacks will incur at no cost [18]. For example, the recent website defacement of Rajasthan Tourism by Iranian hacktivist groups etc.

The Shift: Joint Doctrine for Cyberspace Operations (2024)

A significant pivot occurred in 2024 with the release of the Joint Doctrine for Cyberspace Operations (JDCO) by the Chief of Defence Staff (CDS).

India’s Joint Doctrine for Cyberspace Operations, August 2025. | Ministry of Defence.

● Key Features:The JDCO is a military instrument that outlines a "unified approach" to defend national cyberspace interests. Crucially, it integrates offensive and defensive capabilities.[23]. It emphasises "threat-informed planning," "real-time intelligence integration," and the development of a "common lexicon" for the tri-services.

● Significance:This was the first official acknowledgement of an offensive military cyber posture. By declassifying aspects of this doctrine, India engaged in deterrence signalling - communicating to adversaries that the Indian Armed Forces are authorised and preparing to conduct operations in the cyber domain.

● Limitations:The JDCO is limited to the military. It does not cover the civilian critical infrastructure (power, banking) that is the primary target of grey-zone warfare, nor does it resolve the command-and-control friction between civilian agencies (CERT-In) and military agencies (DCyA)[19] .

International Norms and Sovereignty

India has actively championed the concept of “Cyber Sovereignty” in various eminent international forums such as the Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) and the United Nations Group of Governmental Experts (UN GGE) where India argued that in regard to cyberspace, the applications of principles of the UN Charter including sovereignty and non-intervention fully apply [25].

● Data Sovereignty and Implication for Deterrence: India's stance connects cyber deterrence to "data ownership," contending that security requires control over domestic data. India establishes the legal foundation for categorising cyber incursions as violations of sovereignty by defining sovereignty tightly. This could allow for the justification of appropriate countermeasures under international law (Article 51 self-defense) [26][27].

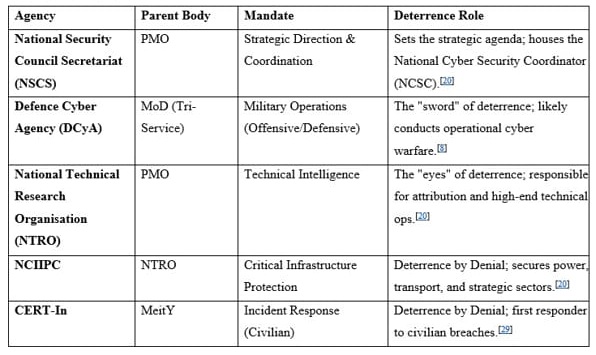

Institutional Architecture: Governance and Coordination

For any nation to have an effective deterrence stance requires it to follow a “Whole-of-Government” approach. Today, the majority of the most critical agencies in India are suffering from fragmentation in its cyber governance structure.

The Institutional Ecosystem

The Coordination Challenge: Silos and Turf Wars?

It is essential to understand that the division of labour between these agencies is often blurred from a technical lens standpoint.

● Civil-Military Disconnect: The DCyA, which defends the military, and the NCIIPC, which safeguards vital/critical infrastructure, differ significantly. The military's role is unknown in the event that a Chinese actor assaults or attacks the public electrical grid, as happened in Mumbai in 2020. When a civilian entity is attacked, does the DCyA respond by retaliation? This question remains unanswered due to the absence of published NCSS guidelines [15].

● Bureaucratic Friction: Reports indicate tension between the MHA (internal security) and MeitY (technology) over control of nodal agencies like CERT-In [21]. This slows down "attribution" - the process of naming the attacker - which is essential for deterrence by punishment.

● Recent Reforms: The 2024 amendment to the Allocation of Business Rules attempted to fix this by designating the NSCS as the nodal agency for "overall coordination and strategic direction,"which potentially is being misinterpreted as empowering the NCSC to act as a central commander during crises.

Credibility Assessment: Capability and Capacity

It is essential to understand that deterrence is a product of capability and will. Even if the political will exists, without the technical capability to deny attacks or inflict punishment, deterrence fails.

Deterrence by Denial: The Resilience Deficit

India’s ability to "deny" success to adversaries is currently its weakest link.

● Vulnerability of Critical Infrastructure: India's critical information infrastructure (CII) is vulnerable, as evidenced by high-profile breaches like the ransomware attack on AIIMS [9](attributed to the Chinese group ChamelGang) and the RedEcho incursion into the electricity industry. Terabytes of patient data were stolen by the AIIMS breach, which revealed a lack of basic hygiene in key institutions [10].

● Supply-Chain Dependence: India is still primarily reliant on foreign software and hardware, mostly from China, the United States and others. Legacy infrastructure is still susceptible to "backdoors" despite the government's introduction of the National Security Directive on Telecommunication Sector (NSDTS) to establish a "Trusted Sources" list for telecom equipment [41][42] [43] [44][45].

Deterrence by Punishment: The Offensive Gap

Does India have the "teeth" to deter?

● Global Rankings:International assessments place India in "Tier Three" of cyber power. The Belfer Center’s National Cyber Power Index ranks India 21st, noting a lack of demonstrated high-end offensive capabilities compared to the US, China, or Russia.[34]The IISS Cyber Capabilities and National Power report echoes this, characterising India’s offensive capabilities as regionally effective (Pakistan-focused) but relying on partners for wider reach.[8]

● The Attribution Struggle:Effective punishment requires rapid attribution. In the case of the Mumbai power outage and AIIMS attack, official attribution was slow or non-existent (often coming from US firms like Recorded Future rather than the GOI)[46]If India cannot publicly prove who attacked, it cannot justify a counter-strike to the international community.

RedEcho targets ten Indian power grid assets and two ports. | Recorded Future.

● Asymmetry with China:Against Pakistan, India possesses "escalation dominance" due to superior resources. However, against China, the asymmetry is stark. Retaliating against China’s superior cyber infrastructure carries the risk of a disproportionate counter-strike that India’s fragile civilian networks likely cannot withstand.[3]

Escalation Risks: The South Asian Nuclear Nexus

It is important to note that cyber deterrence in South Asia cannot be viewed in isolation; it operates under the shadow of nuclear weapons.

Cross-Domain Deterrence (CDD)

Scholars debate the utility of Cross-Domain Deterrence - using threats in one domain (for example, conventional or nuclear) to deter actions in another (cyber).11

● The India-Pakistan Trap:Research scholars and Pakistan defence analysts view India’s JDCO as highly destabilising.[17]According to CISS Pakistan, the argument stands that India might use a cyberattack (or a "false flag" cyber event) as a pretext for a kinetic strike (for example, a BrahMos missile launch).

● Inadvertent Escalation:The risk of misinterpretation is usually high when it comes down to Pakistan. A cyberattack intended to disrupt a specific radar installation for instance could be viewed by the adversary as the blinding phase of a nuclear first strike. This happens when political lens bypasses proper strategic thinking. Pakistan believes that in a crisis (like Pulwama-Balakot), the "fog of war" amplified by cyber disruption could lead to rapid, unintended nuclear escalation.[5]

● The Illusory Truth Effect:Deep fakes, disinformation campaigns (Cognitive Warfare) and influence operations can force leaders into corners. If a deep fake circulates showing an Indian leader threatening war, Pakistan might mobilise, wanting to trigger a real war. This "weaponisation of information" is a key concern in the Pakistani critique of India's doctrine.[17].

Despite ongoing criticism from Pakistan, India's strategy to cross-domain operations emphasises excellent escalation control, doctrinal maturity and strategic prudence rather than recklessness or destabilising intent. India's stance shows a clear grasp of escalation thresholds and signaling discipline, even though academics are still debating the effectiveness of cross-domain deterrence, particularly the employment of cyber or informational operations to influence conduct in the conventional or nuclear domains.

Instead of creating pretexts for kinetic conflict, Indian policy, particularly the developing Joint Doctrine for Cyberspace Operations, aims to improve deterrence through denial and resistance and is continuing improvement in that space. Claims from Pakistani experts that India would use a cyber crisis or conduct a "false flag" operation to justify a kinetic strike tell more about Pakistan's projection and insecurity than about Indian intent.

The so-called "India-Pakistan trap" assumes that New Delhi is prone to impulsive escalation or poor judgment. The reverse is suggested by empirical data. India showed measured use of force, unambiguous political authority over military operations, and purposeful signals intended to de-escalate after goals were met, even during high-intensity crises like Pulwama–Balakot. India's strategic culture places a strong emphasis on controllability and proportionality, which lessens the possibility that cyber operations, whether defensive or offensive, might be mistaken for nuclear first strike preparations. This is exactly where India's advantage is found: a more cohesive civil-military decision-making framework, increased trust in second-strike capabilities, and a better capacity to handle uncertainty without escalating out of fear.

Indian planners actively consider concerns about unintentional escalation and the "fog of war," especially in the cyber sphere. Due to lower thresholds, doctrinal opacity, and a historical dependence on quick escalation to overcome conventional disparity, Pakistan itself finds it difficult to control escalation risks. This is reflected in India's emphasis on redundancy, resilience, and attribution caution. India's strategic depth enables it to handle such interruptions as tolerable annoyances rather than existential triggers, preventing it from becoming destabilised by cyber uncertainty.

In a similar vein, Indian leadership is not forced to make snap judgments by the prospect of cognitive warfare, which includes deepfakes, misinformation, and narrative manipulation. The illusory truth impact that Pakistani experts worry about is mitigated by India's strong institutions, diverse media landscape, and expertise in handling information disorder. Pakistan's emphasis on media weaponisation as a priority highlights an asymmetry: Pakistan is still more susceptible to narrative-driven mobilisation pressures, but India is less reliant on manufactured crises for strategic relevance.

India avoids a Pakistani escalation trap since it is not required to. Its strong conventional and technological capabilities are only one aspect of its strategic strength; other factors include confidence, restraint, and escalation control. India uses stability to counter Pakistan's dread of uncertainty, whereas Pakistan perceives destabilisation as planned competition. In the end, this psychological, ideological and institutional asymmetry strengthens India's position as the dyad's more potent and strategically advanced actor.

The China Dynamic: Salami Slicing

Vis-à-vis China, the risk is not immediate nuclear escalation but likely "strategic erosion." China uses cyber tools to "salami slice"- taking small aggressive actions that do not justify a war but cumulatively degrade India’s security.[3]India’s lack of declared "red lines" encourages this behaviour. If India attempts to deter China through offensive cyber retaliation, it risks exposing its own digital dependence, potentially leading to massive economic disruption.[36]

Strategic Partnerships: The Force Multiplier

India has increasingly relied on alliances to strengthen deterrence after realising its own limitations.

● US-India Cooperation: Supply chain security and the exchange of cyber threat intelligence are the main goals of the TRUST project and the iCET (project on Critical and Emerging Technology) [20]. Separately, unrelated to this, in the past, companies such as Recorded Future supported attribution (for example, identifying Chinese malware in Indian grids) and are still continuing to do so by providing critical insights into threat intelligence feeds that is proprietary called “Malicious Traffic Analysis” to Indian enterprises.

● Alignments in diplomacy: The goal of India's participation in the Quad and cyber talks with the UK, France and Japan should be to establish a "collective deterrence" framework in which an attack on one is denounced by all, increasing the consequences to the attacker's reputation.

Policy Recommendations

The following evidence-based policy initiatives are suggested in order to close the credibility gap and create a strong deterrence posture:

● Immediate Promulgation of the NCSS: The National Cyber Security Strategy must be released by the government after interministerial and other associated deadlocks are resolved. This document must resolve the detrimental "strategic ambiguity" by outlining India's position on the threshold of "armed attack" in cyberspace.

● Operationalise "Red Lines": India should enact a declaratory policy that clearly connects cyberattacks on Critical Information Infrastructure (CII), particularly power grids, healthcare, and nuclear command and control, to Cross-Domain Retaliation. This lets adversaries know that some targets are off-limits and that cyberattacks will not be the only reaction.

● Upgrade the DCyA to a Cyber Command:In contrast to the traditional services' rotating personnel, the Defense Cyber Agency ought to be transformed into a full-fledged Cyber Command with autonomous budgetary authority and a permanent cadre of cyber-warriors (technical reservists). This guarantees operational preparedness for sophisticated offensive actions.

● Institutionalise Attribution: To lessen its reliance on foreign private companies, India has to invest in sovereign attribution capabilities (intelligence and forensics). Attacks that are publicly attributed (also known as "naming and shaming") cause harm to one's reputation and, in accordance with international law, justify countermeasures.

● Civil-Military Integration: To guarantee a coordinated and prompt response in the case of a national catastrophe, the NSCS must operationalise a joint command center that unifies the DCyA (military offense) and the NCIIPC (civilian defence).

Conclusion

India is at a pivotal point in its history. The deterrence equation in South Asia has been drastically changed by the weaponisation of the internet, leaving India less-likely vulnerable to asymmetric disruption from Pakistan and "grey zone" coercion from China. The lack of a unified National Cyber Security Strategy, disjointed governance, and a "denial deficit" in critical infrastructure continue to limit the overall national deterrence framework, even though the publication of the 2024 Joint Doctrine for Cyberspace Operations indicates a developing military posture.

Due to the risks of escalation and technological disparity, the research indicates that India currently lacks a credible deterrence by punishment capability against China. However, if it can overcome bureaucratic slowness and use its strength in the private sector, it has a great chance of achieving deterrence by denial.

The way forward necessitates a shift from ambiguity to clarity: showing not only the ability to resist attacks but also the political resolve to demand a price for them. Cyber weakness is provocative in the harsh Indo-Pacific region; only an offensive-capable, resilient and integrated India can expect to fend off the impending digital challenges.

(Exclusive to NatStrat)

Endnotes